Kumasi,18 February 2026– Brainsfield Ltd. has expanded its operational coverage within the Ashanti Region of the Electricity Company of Ghana(ECG),effective today.

The expansion brings Brainsfield’s services to the Ayigya District and Ejisu District, following the company’s extension in Kwabre District in 2025.These expansions are being undertaken at the request of the Ashanti East Regional General Manager, Ing. Daniel Mensah Asare.

The latest coverage increases responds to identified shortfalls in meter supply across the affected districts and forms part of ECG’s broader effort to stabilize service delivery and reduce losses within the region under the Loss Reduction Programme (LRP).

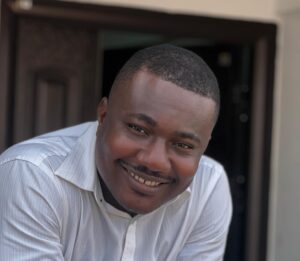

“This expansion reflects our operational readiness to support ECG where capacity gaps exist, particularly in districts experiencing supply constraints,” said Maclean Kajola Dzormekuh, Project Manager at Brainsfield Ltd. “Our focus remains on timely deployment, compliance with technical standards, and sustained service delivery.”

Throughout the ongoing challenges within the energy sector, Brainsfield Ltd. has continued to operate as a dependable partner to ECG, guided by the strategic direction of its Chief Executive Officer, Winfred Kumah Apawu.

With the expanded coverage, Brainsfield will deploy its BY-100C single-phase meters and BY-300C three-phase meters to additional customers across the Ashanti Region, bringing with them the company’s commitment to innovation, transparency, and measurable impact.

The company remains active in the Manhyia District, where more than 97 percent of paid-up applicants have been served since December 2024. Replacement of faulty and obsolete meters in the district is also ongoing.

Maclean is the Project Manager for Brainsfield's energy metering projects. He is a business development manager who believes in the power of the build-measure-learn feedback loop, and mankind's inherent ability to evolve through mentorship and self-motivation.